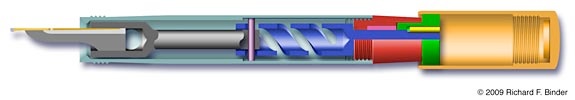

One of the problems with Waterman-type safeties is the tubular shaft that drives the nib in and out. It has a couple of slots cut in its wall, and it’s fragile. In this cross-sectional drawing, the shaft is the blue part.

The slots in this pen’s shaft are long helical cuts. The purple crosswise pin is riding in slots that run along the inside of the barrel. As the green operating knob turns the shaft, the slots in the shaft force the pin to move along the barrel slots, extending or retracting the nib. You can see the potential here for breakage if too much force is applied in an attempt to move a nib that’s stuck.

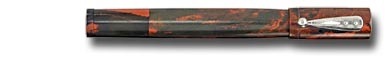

Waterman started producing safeties in 1907 or 1908. The earliest version of Waterman’s safety had its mechanism “backwards,” with the helical slots running along the barrel wall while the straight slots were cut into the tubular shaft. These earlier pens are relatively uncommon, and you can identify them by seeing whether the nib spins around as it moves in and out. If it does, the pen is an early one. The early pen shown here is a Nº 15VS.

When this pen came into my hands, its shaft was broken. Somebody had turned it too hard, and its slots had both split at the end closest to the nib. When the shaft is split in this manner, the pen will work, sort of, but it’s always at risk. However, replacement parts are extremely thin on the ground. I certainly had none for this pen. So I had to repair the shaft I had. It was actually a quick repair, and it should last as long as the pen, if not longer.

Step 1 was to take a couple of quick measurements. It turned out that the shaft’s outside diameter was very close to that of a stock size of styrene tubing. So I cut a collar from the styrene tubing. For safety, I found a drill that fit inside the tubing and chucked that drill up in the lathe tailstock to keep the tubing from flexing and shattering when the cutoff tool penetrated its wall thickness.

With the collar cut, I very carefully protected the shaft by cutting a short length of brass tubing and turning down so that it fit very closely inside the shaft’s tubular section and also splitting a length of styrene tubing to make a protective layer for the outside. I chucked up the well-protected shaft in the lathe and turned down the end just enough that my collar would slip easily onto it.

There is no known way to repair an old break in hard rubber because no adhesive will stick strongly enough to its oxidized surface. But a surface that’s newly exposed to air hasn’t oxidized yet, and adhesives will stick to it. I epoxied the styrene collar onto the end of the shaft, cleaned off the excess epoxy, allowed the epoxy to set, and used an X-acto knife to shave away the tiny bit of styrene that was impinging into the end of each of the two slots.

And that’s all there was to it. With the hard part out of the way, I restored the shaft packing. Here are the pen’s guts all reassembled and ready to install into the barrel.

That’s one pen that won’t have to climb up onto the junk heap.